From prototype to strategic direction; the journey of an idea that's still unfolding.

I think it's a great idea, but I don't see the use case.

That's what Guillaume, Pictarine's CEO, told me after I'd spent weeks building momentum for Picta for Kids; an idea that had sparked hallway debates, pulled in a Product Designer volunteering his time, and gotten parents across the company genuinely excited about something that didn't exist yet.

In the span of one meeting, an idea that felt ready to ship became something else: a seed planted for the future.

This is the story of how I pitched, prototyped, and rallied a company around a product that never made it to the roadmap. It's about the gap between internal enthusiasm and executive conviction and what happens when you can't bridge it with data you don't have yet.

First, some context

Let me start with where I work, because it matters for understanding how this idea came to life.

Pictarine is a photo printing company with over 35 million app downloads, built on a simple premise: printing your photos should be as easy as taking them. The company is bootstrapped, which means every resource decision is deliberate. We've recently launched innovations like partnerships with Walgreens for Picta Studio, an Apple Vision Pro app for selecting photos in spatial computing.

I work as a Growth Marketing Manager at Pictarine. The company operates in squads, dedicated teams built around strategic priorities. There's no room for side projects so if you want to build something new, you need a squad. And squads only form around priorities that align with the company's strategic roadmap.

This is important context because Picta for Kids wasn't born in a strategy meeting or validated through market research. It started the way most side ideas do: with a random observation that wouldn't leave me alone.

And somehow, I convinced myself it deserved its own squad.

The Spark

I was thinking about buying screen-free cameras for my twins when it hit me: the hardware market for kids' cameras is massive: VTech, Kidamento, Polaroid Instax, etc. but there's no photo printing service designed exclusively for children.

Parents buy millions of these cameras every year. Kids take hundreds, sometimes thousands of photos. And then... what? The photos sit on a device, or parents print them through their own accounts using interfaces built for adults.

That was my aha moment: Picta for Kids.

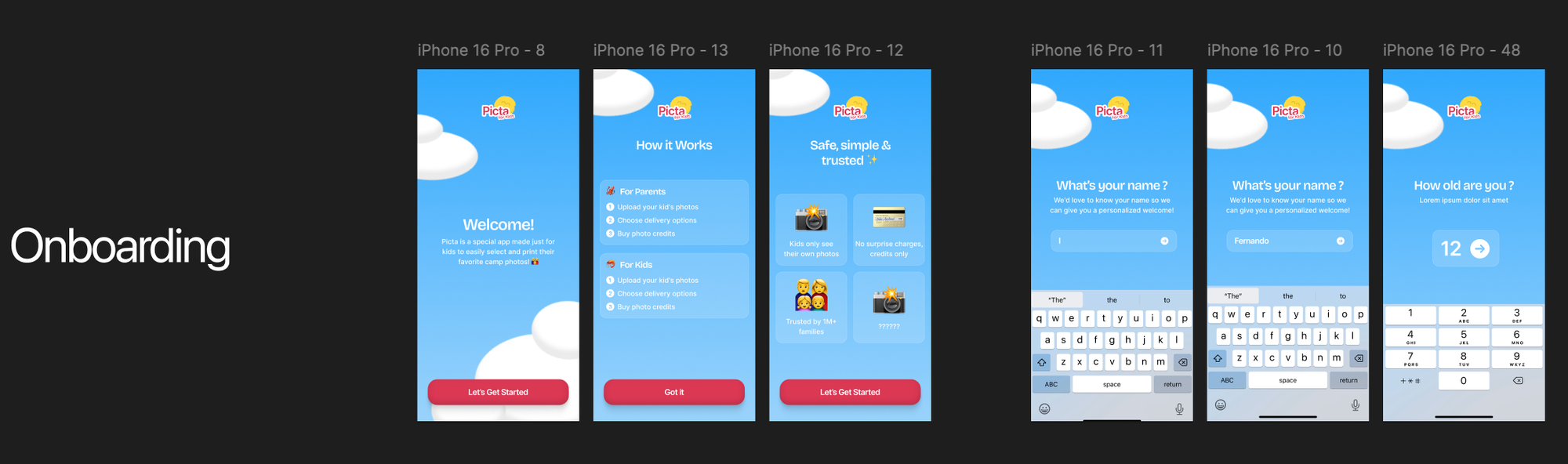

Not just a kid-friendly version of our existing photo printing app. A completely separate experience, designed for children to browse their photos, eventually personalise them with stickers, and order prints autonomously (with parental credit controls, obviously).

The interface would adapt as they grew:

- Ultra-simple for 6-10 year olds: pick photos, add stickers, done.

- Progressively more sophisticated for tweens: posters, cards, layout options.

- Nearly adult-level features by age 13-15.

The core idea: let kids own the experience. They choose. They design. They order. Parents supervise through credits and approvals, but the creative control belongs to the child.

The idea felt obvious once I saw it. Which made me wonder: why hasn't anyone done this yet?

When a designer joins the mission

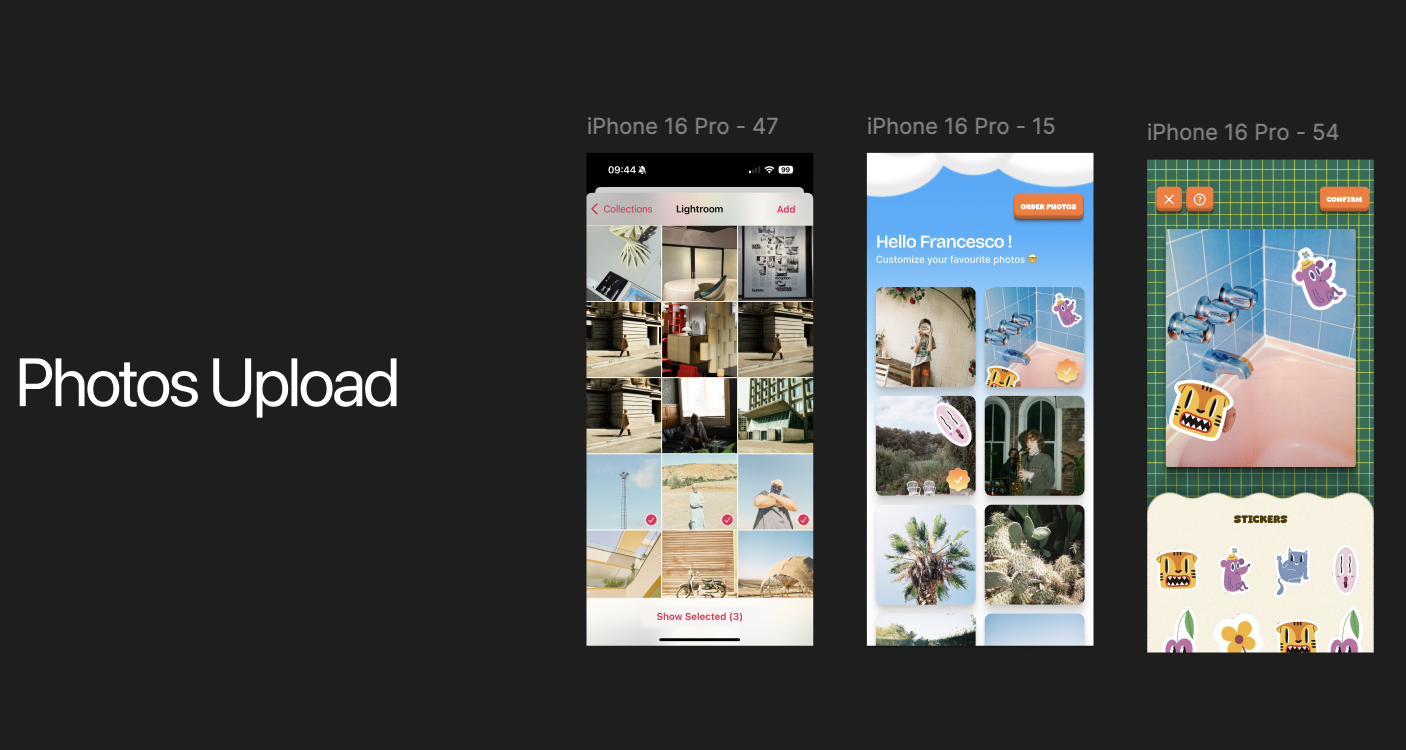

I'd already built one successful prototype using Lovable (an AI coding tool), so I decided to try again, this time to bring Picta for Kids to life.

What I loved about the process was how it forced clarity. You can't prompt an AI with vague ideas; you have to articulate exactly what you want. With each iteration, I refined my thinking. The back-and-forth made me confront gaps in my logic and think through edge cases I hadn't considered.

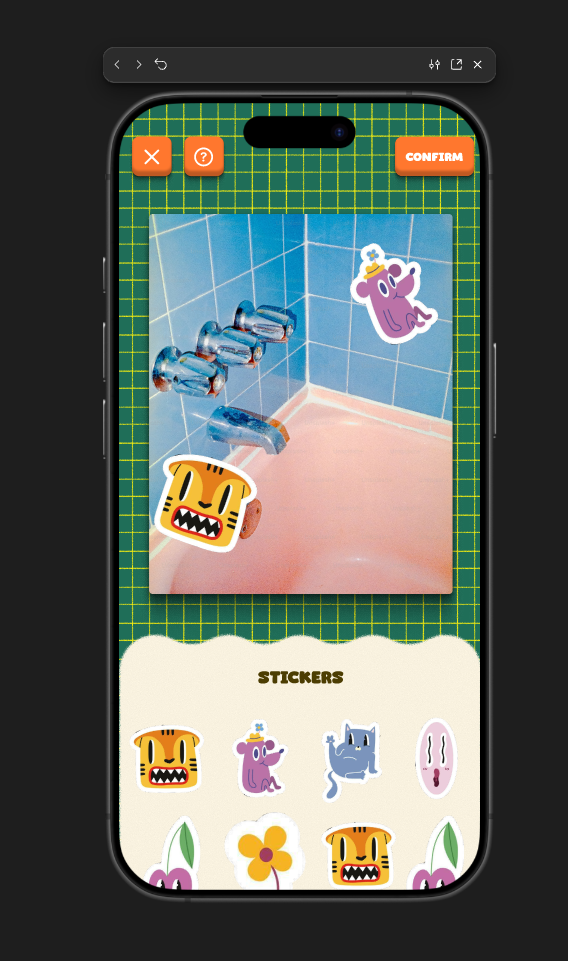

In a surprisingly short time, I had a working prototype. Emphasis on working because it was functional but ugly. Really ugly. But it demonstrated the core flow: photo selection, sticker overlay, order placement with parental credits.

Attention les yeux! Test it in mobile format.

I scheduled a meeting with Max, our co-founder and CMO, to walk him through it.

His reaction:

I'm thinking about so many things at once.

Later, Max explained his thought process when hearing the idea:

I went through my usual stages: First, this is so cool, it's like Apple targeting students. Second, why isn't anyone doing this? Is it a false good idea? Third, what quick tests can we run to validate interest?

He loved the idea. More importantly, he told me to talk to parents at Pictarine to understand how their kids currently take and print photos, and whether this concept resonated.

I was energized. That same day, I posted in our internal Slack channel for parents, inviting them to a demo the following Thursday.

And then something unexpected happened.

Vincent, one of our Product Designers, sent me a message:

Love the Picta for Kids idea. I don't really know what form it takes or what stage it's at, but if you need design help, let me know.

He hadn't seen the prototype yet. He'd only read the name.

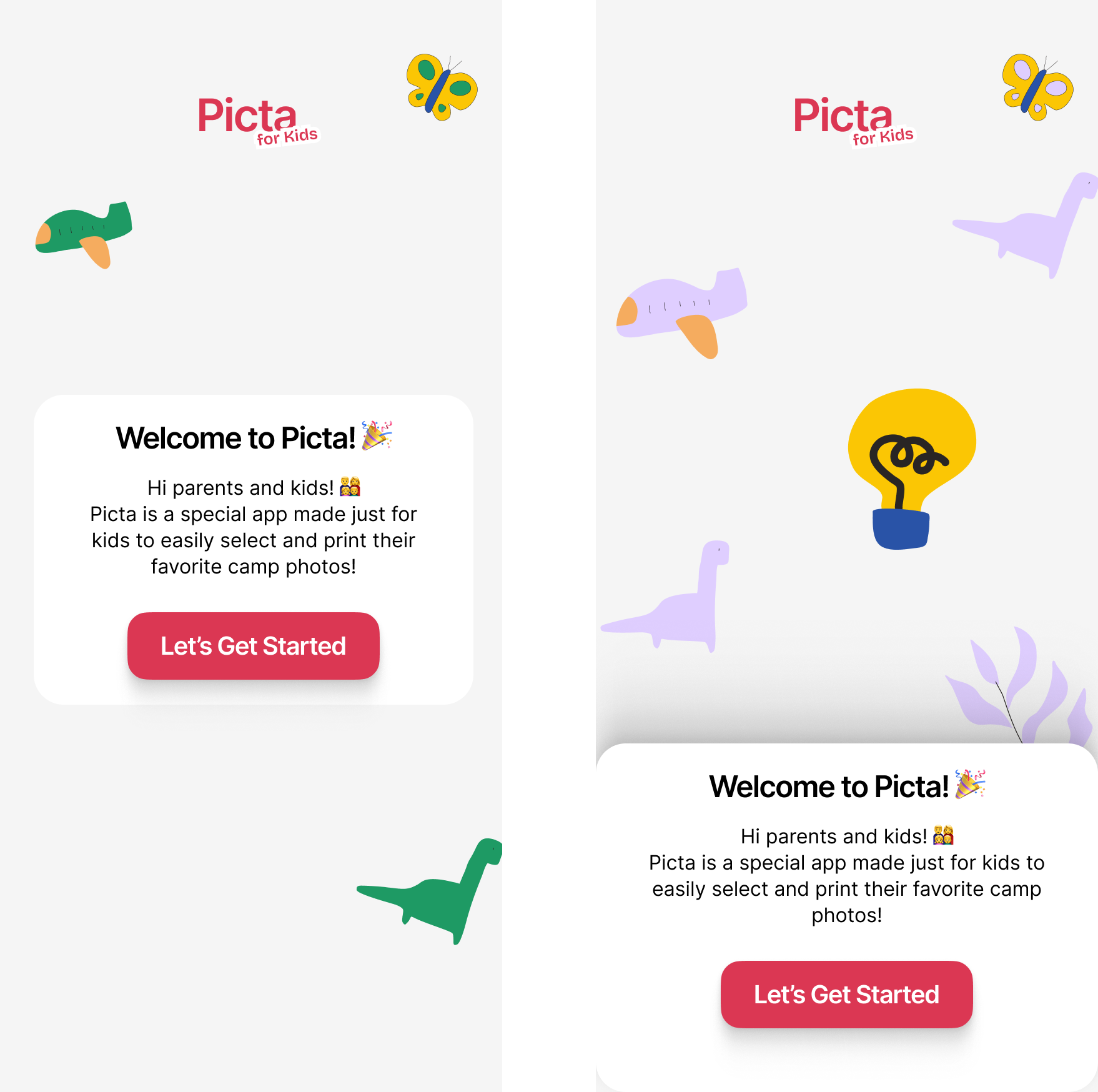

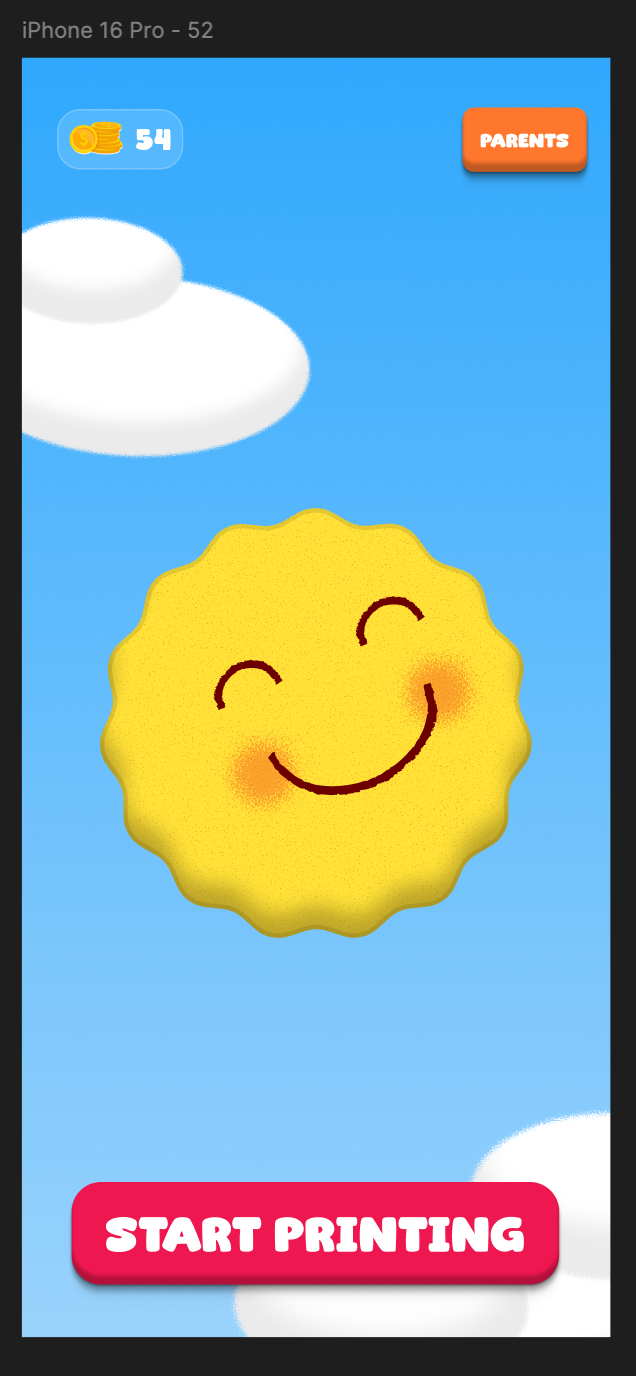

Within ten minutes of our first conversation, he'd recreated the first screen in Figma. By that evening, he'd rebuilt the entire prototype with pixel-perfect design, a cohesive visual identity, and thoughtful solutions to edge cases I hadn't even noticed.

This is the moment everything changed. Picta for Kids went from Alice's side idea with an ugly prototype to something that looked like it could ship tomorrow. Vincent gave it an identity. And in an open-plan office, his work didn't go unnoticed.

But here's what really showed his investment: over the next weekend, Vincent went to the grocery store and photographed a package because the illustration reminded him of Picta for Kids. He thought it could become the mascot; a friendly guide to help kids navigate the app.

We talked it through and added the mascot to the prototype. It wasn't just about aesthetics; it was a functional decision. Kids needed a companion, something that made the experience feel safe and guided.

And from a marketing perspective? It clicked everything into place. The app suddenly had a complete identity; something distinctive, ownable and easy to communicate. This wasn't just a feature set anymore. It was a brand.

Later, when I asked Vincent what made him so invested in this project, his answer captured exactly why Picta for Kids felt different:

It opened up a rare creative playground in today's app ecosystem, a space where craft and fun could take center stage. The kids' world lets you break the usual codes of sobriety that have become standard and dare to take more expressive, playful, colorful stances. I wanted to create lively interfaces, full of personality and depth, a bit like what Andy Allen does with NotBoring Software.

Vincent wasn't assigned to this project. He wasn't asked to spend his weekend thinking about it. He just... cared.

People started asking questions. The curiosity spread beyond parents.

Inspiration.

People start caring

The parent presentation drew more than just parents. Word had spread, and my audience included people from across the company who were just curious about what this thing was.

I walked through the Figma prototype, and the feedback came fast: constructive questions, new ideas, healthy debate.

The most recurring concern:

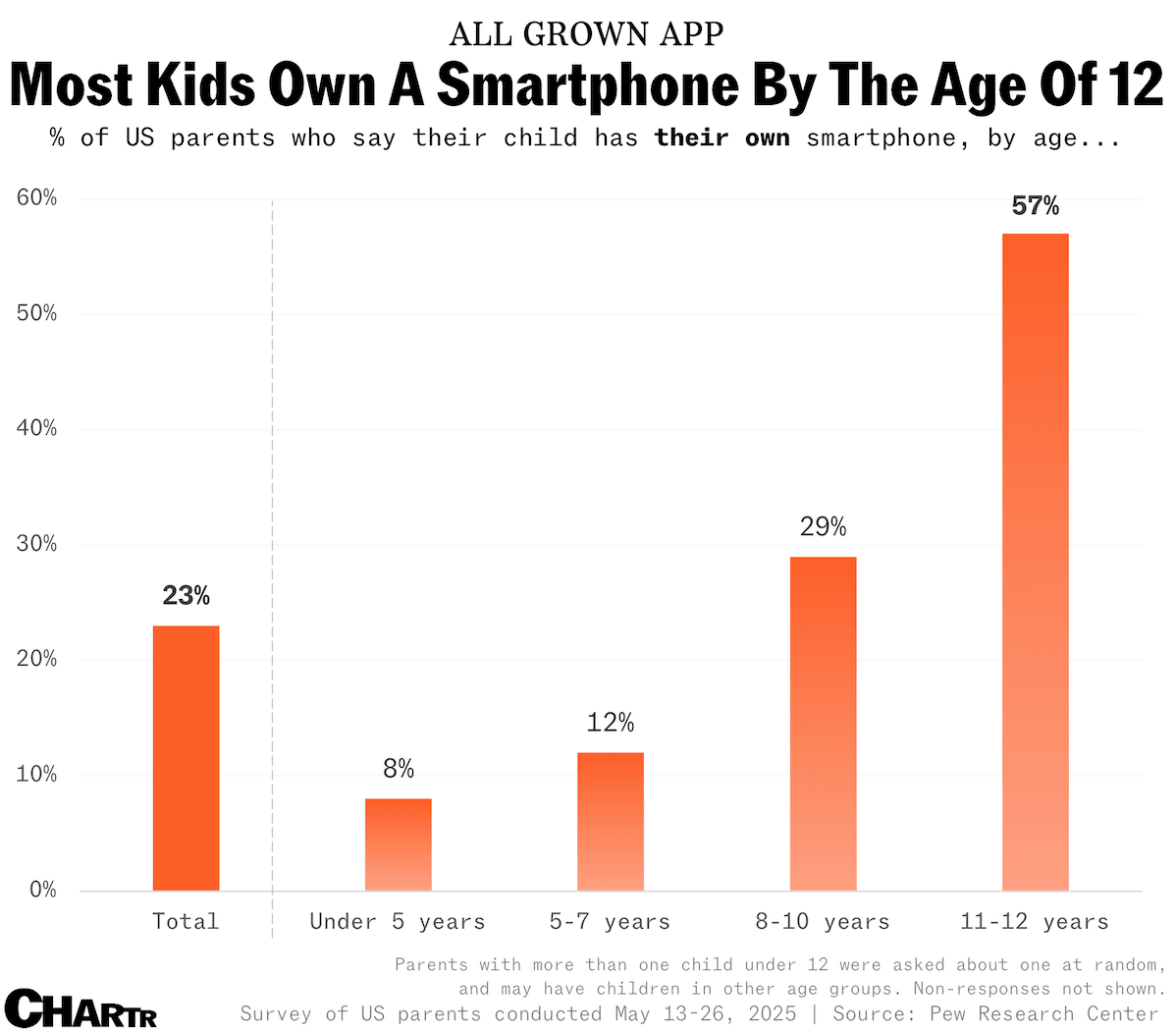

Aren't we just putting kids in front of screens? How comfortable are we with that?

My answer: They're already on screens. Statistically, a lot. Several weeks later, I'd come across this graph from Sherwood News that made the point better than I ever could:

At least with Picta for Kids, they'd be in a safe environment, interacting only with their own memories. No ads, no algorithms, no endless scroll. Just their photos.

The discussion reinforced something I hadn't fully articulated before: this wasn't just a product idea. It was about giving kids agency over their creativity in a controlled and intentional way; something parents genuinely cared about.

Then came François, our COO.

His reaction:

Why didn't we think of this sooner?!

François saw opportunities I hadn't even considered. Apple App Store featuring! Apple loves highlighting educational, creative tools for kids.

That's when I saw a strategic differentiation for our European expansion. Early brand loyalty that could last decades.

And then he said something that floored me: he wanted to act as a light Product Manager for the idea. This wasn't just enthusiasm, he was willing to put his weight behind it.

But he was also realistic. All our squads were fully allocated. If Picta for Kids was going to happen, it would need to become a squad itself. Which meant proving it deserved to exist alongside our strategic priorities.

He asked me to write a synthesis document for Product Leadership. So I did.

I laid out:

- Market opportunity: kids' camera market exploding, zero printing apps built for children.

- Product vision: age-adaptive UX, parental credits, mascot-guided experience.

- Strategic value: early brand loyalty, European market differentiation, potential Apple featuring.

- SWOT analysis: clear strengths (virgin market, existing infrastructure), honest weaknesses (kids screen times), real opportunities (9% annual growth in kids' photo market), genuine threats (competition from instant cameras, uncertain teen adoption).

The document made the rounds. People started mentioning Picta for Kids in conversations I wasn't part of (I consider it as my biggest win so far). It had become a reference point, something the company was actively thinking about.

It felt like momentum. Real momentum.

The CEO meeting & reality check

I knew the CEO meeting mattered. Not because Guillaume would kill the idea or greenlight it on the spot, but because I needed to make the case that Picta for Kids deserved to disrupt our strategic priorities.

That's what I hadn't fully grasped yet: in a company organised in squads around strategic roadmap items, you're not just pitching an idea. You're asking the company to reshuffle its resources and priorities for something unproven.

I also knew I needed to be careful with my words. In preparation meetings, I'd been advised to focus on the use case, the market validation, the business model but not the origin story or my personal enthusiasm.

Naturally, I did the exact opposite.

I spent too much time on how the idea came to me, the prototyping journey, Vincent's weekend grocery store epiphany. I thought the narrative would help Guillaume see what I saw: that it was a movement inside the company.

In hindsight, I can see myself in that meeting: animated, passionate, explaining the journey when what he needed was the destination. If there was an award for most effective way to add confusion while trying to provide clarity, I would have won it that day.

What I gave him was context without clarity.

His response was measured:

I think it's a great idea, but I don't see the use case.

At that moment, I heard it as a no. But what I didn't realise was that Guillaume was actually thinking deeply about the opportunity.

As he later explained:

When Alice presented her idea to me, I was amazed by how far she had gone in her thinking, she had literally built an MVP along with a business model. It took me several days to assess the opportunity and figure out the impact on our company's roadmap.

Several days. Not several minutes to dismiss it, but several days to seriously consider it.

What I had was enthusiasm, internal validation, and a strong synthesis document. What I didn't have yet was proof that parents would actually use it, or that the unit economics made sense for the investment required.

As Max put it:

What Guillaume and I discussed was this: it's the kind of idea aligned with the company's mission, but can't be prioritized on the product roadmap in the medium term. Could it be approached as a marketing operation first?

That was the real question. Not is this a good idea? but is this the right idea right now, with the resources we have and the priorities we've set?

The answer was: not immediately. But the conversation didn't end there.

The Product Leadership team discussed it. And they agreed: in the coming years, we would open exploration into the kids market.

Picta for Kids didn't get a squad right away. But it opened a door. It planted a seed. It made kids a legitimate strategic consideration for the future.

Sometimes an idea's impact isn't immediate execution but it's shifting how a company thinks about what's possible.

What this taught me

So what did I learn from watching an idea go from weekend prototype to company-wide conversation to shelved indefinitely?

1. Internal enthusiasm is not the same as market validation.

Everyone at Pictarine loved Picta for Kids. Parents got excited. A Product Designer volunteered his time. The COO wanted to act as Product Manager. But none of that proved customers would pay for it.

Internal validation feels like momentum. It is momentum but just not the kind that answers a CEO's question about business viability. I had proven the idea was compelling to people who already understood photo printing and Pictarine's value proposition. I hadn't proven it was compelling to parents scrolling the App Store who'd never heard of us.

2. Bottom-up innovation in scale-ups requires a different kind of proof.

In a startup, you can hack together an MVP and test it in the wild. In a scale-up with squads built around strategic priorities, you need to prove an idea deserves to disrupt the roadmap before you build it.

That's not wrong, it's responsible resource allocation. But it creates a catch. How do you prove demand for something that doesn't exist without building it first?

The answer, I think, is finding the smallest possible test that produces a strong signal. In our case: social ads experiments. Mock landing pages. Waitlist signups. Something cheaper than a full squad but more concrete than a Figma file.

3. Passion can blur your pitch.

I walked into that CEO meeting thinking the story of how Picta for Kids came together would make Guillaume see its inevitability. Instead, I buried the business case under narrative.

The irony: I work in growth marketing. I know how to communicate value propositions. But when you're emotionally invested in an idea, clarity becomes harder. You assume people will connect the dots the way you did. They won't.

If I could do it again, I'd lead with the problem and the market gap, then show the solution. The journey is compelling, but it's not the pitch.

4. Ideas don't die.

Picta for Kids didn't get a squad. It didn't make the immediate roadmap. But it did something more subtle and perhaps more valuable: it opened a new field of thinking and influenced our strategic direction.

Guillaume spent time thinking about this idea. The Product Leadership team discussed it. And they agreed to explore the kids market in the coming years.

That's not the win I expected when I started building prototypes. But it might be a more important one, one I'm the most proud of.

Sometimes an idea's impact isn't about immediate execution but changing what a company considers possible. It's about planting a seed that grows into a strategic direction.

The question isn't always will this ship? sometimes it's will this change how we think about where we're going?.

What do you think?

For now, Picta for Kids lives in a Figma file and a Notion synthesis. Vincent's mascot still sits there, waiting to guide kids through an app that doesn't exist yet.

And I'm genuinely curious: Would you use something like this?

If you're a parent or if you work with kids, or if you remember being a kid with a camera and wishing you could do more with those photos, please leave a comment.

Tell me if this is something you'd want. Tell me if I'm solving a problem that doesn't actually exist, or if there's a real use case here that we just haven't proven yet.

Because maybe the data I need to bring this idea back is sitting in the comments section of this article!

What's funny about sharing this idea here is that my team asked me: "aren't you afraid a competitor will steal your idea?" That's a possibility, and honestly, I'd be pissed about it but that would also represent the best interest measure ever!

Comments ()